MainFrame

Commerce Choi Kwang Do and Malaria

Commerce Choi Kwang Do is a participating school in the Choi Kwang Do Martial Arts International/Malaria Foundation

International partnership to help combat malaria. Our students are raising money on their own and through events to

help. Students have a coupon book - if someone donates at least $1 that person receives a coupon that allows

them to train for free for one month at any participating Choi Kwang Do School.

If you would like to know more about malaria, keep reading through the bottom of this page...

What is Malaria?

Malaria is a vector-borne infectious disease that is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of the

Americas, Asia, and Africa. It causes disease in approximately 500 million people every year and kills between one and three

million people every year, mostly young children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria is commonly-associated with poverty, but is

also a cause of poverty and a major hindrance to economic development.

Malaria is one of the most common infectious diseases and an enormous public-health problem. The disease is caused by

protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. The most serious forms of the disease are caused by Plasmodium falciparum and

Plasmodium vivax, but other related species (Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae, and sometimes Plasmodium knowlesi) can

also infect humans. This group of human-pathogenic Plasmodium species are usually referred to as malaria parasites.

Malaria parasites are transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes. The parasites multiply within red blood cells, causing

symptoms that include symptoms of anemia (light headedness, shortness of breath, tachycardia etc.), as well as other general

symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, flu-like illness, and in severe cases, coma and death. Malaria transmission can be

reduced by preventing mosquito bites with mosquito nets and insect repellents, or by mosquito control by spraying insecticides

inside houses and draining standing water where mosquitoes lay their eggs.

Unfortunately, no vaccine is currently available for malaria. Instead preventative drugs must be taken continuously to reduce

the risk of infection. These prophylactic drug treatments are simply too expensive for most people living in endemic areas.

Most adults from endemic areas have a degree of long-term recurrent infection and also of partial resistance; the resistance

reduces with time and such adults may become susceptible to severe malaria if they have spent a significant amount of time in

non-endemic areas. They are strongly recommended to take full precautions if they return to an endemic area. Malaria infections

are treated through the use of antimalarial drugs, such as quinine or artemisinin derivatives, although drug resistance is

increasingly common.

History of Malaria

References to the unique periodic fevers of malaria are found throughout recorded history, beginning in 2700 BC in China

during the Xia Dynasty. The term malaria originates from Medieval Italian: mala aria — "bad air"; and the disease was

formerly called ague or marsh fever due to its association with swamps.

Scientific studies on malaria made their first significant advance in 1880, when a French army doctor working in Algeria

named Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran observed parasites inside the red blood cells of people suffering from malaria. He

therefore proposed that malaria was caused by this protozoan, the first time protozoa were identified as causing disease.

For this and later discoveries, he was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. The protozoan was called

Plasmodium by the Italian scientists Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli. A year later, Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor

treating patients with yellow fever in Havana, first suggested that mosquitoes were transmitting disease to and from humans.

However, it was Britain's Sir Ronald Ross working in India who finally proved in 1898 that malaria is transmitted by

mosquitoes. He did this by showing that certain mosquito species transmit malaria to birds and isolating malaria parasites

from the salivary glands of mosquitoes that had fed on infected birds. For this work Ross received the 1902 Nobel Prize

in Medicine. After resigning from the Indian Medical Service, Ross worked at the newly-established Liverpool School of

Tropical Medicine and directed malaria-control efforts in Egypt, Panama, Greece and Mauritius. The findings of Finlay and Ross

were later confirmed by a medical board headed by Walter Reed in 1900, and its recommendations implemented by William C.

Gorgas in the health measures undertaken during construction of the Panama Canal. This public-health work saved the lives of

thousands of workers and helped develop the methods used in future public-health campaigns against this disease.

The first effective treatment for malaria was the bark of cinchona tree, which contains quinine. This tree grows on the slopes

of the Andes, mainly in Peru. This natural product was used by the inhabitants of Peru to control malaria, and the Jesuits

introduced this practice to Europe during the 1640s where it was rapidly accepted. However, it was not until 1820 that the

active ingredient quinine was extracted from the bark, isolated and named by the French chemists Pierre Joseph Pelletier

and Jean Bienaime Caventou.

In the early twentieth century, before antibiotics, patients with syphilis were intentionally infected with malaria to create

a fever, following the work of Julius Wagner-Jauregg. By accurately controlling the fever with quinine, the effects of both

syphilis and malaria could be minimized. Although some patients died from malaria, this was preferable than the almost-certain

death from syphilis.

Although the blood stage and mosquito stages of the malaria life cycle were established in the 19th and early 20th centuries,

it was not until the 1980s that the latent liver form of the parasite was observed. The discovery of this latent form of the

parasite finally explained why people could appear to be cured of malaria but still relapse years after the parasite had

disappeared from their bloodstreams.

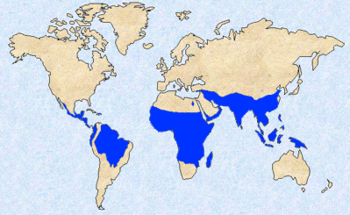

Malaria Distribution and Impact

Malaria causes about 350–500 million infections in humans and approximately one to three million deaths annually — this represents at least one death every 30 seconds. The vast majority of cases occur in children under the age of 5 years; pregnant women are also especially vulnerable. Despite efforts to reduce transmission and increase treatment, there has been little change in which areas are at risk of this disease since 1992. Indeed, if the prevalence of malaria stays on its present upwards course, the death rate could double in the next twenty years. Precise statistics are unknown because many cases occur in rural areas where people do not have access to hospitals or the means to afford health care. Consequently, the majority of cases are undocumented.

Malaria is presently endemic in a broad band around the equator, in areas of the Americas, many parts of Asia, and much of

Africa; however, it is in sub-Saharan Africa where 85– 90% of malaria fatalities occur (see blue shaded area in graphic). The geographic distribution of malaria

within large regions is complex, and malarial and malaria-free areas are often found close to each other. In drier areas,

outbreaks of malaria can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by mapping rainfall. Malaria is more common in rural areas than

in cities; this is in contrast to dengue fever where urban areas present the greater risk. For example, the cities of the

Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia are essentially malaria-free, but the disease is present in many rural regions. By contrast, in

Africa malaria is present in both rural and urban areas, though the risk is lower in the larger cities.

Malaria is presently endemic in a broad band around the equator, in areas of the Americas, many parts of Asia, and much of

Africa; however, it is in sub-Saharan Africa where 85– 90% of malaria fatalities occur (see blue shaded area in graphic). The geographic distribution of malaria

within large regions is complex, and malarial and malaria-free areas are often found close to each other. In drier areas,

outbreaks of malaria can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by mapping rainfall. Malaria is more common in rural areas than

in cities; this is in contrast to dengue fever where urban areas present the greater risk. For example, the cities of the

Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia are essentially malaria-free, but the disease is present in many rural regions. By contrast, in

Africa malaria is present in both rural and urban areas, though the risk is lower in the larger cities.

Malaria is not just a disease commonly associated with poverty, but is also a cause of poverty and a major hindrance to

economic development. The disease has been associated with major negative economic effects on regions where it is widespread.

A comparison of average per capita GDP in 1995, adjusted to give parity of purchasing power, between malarious and

non-malarious countries demonstrates a fivefold difference (US$1,526 versus US$8,268). Moreover, in countries where malaria is

common, average per capita GDP has risen (between 1965 and 1990) only 0.4% per year, compared to 2.4% per year in other

countries. In its entirety, the economic impact of malaria has been estimated to cost Africa US$12 billion every year. The

economic impact includes costs of health care, working days lost due to sickness, days lost in education, decreased

productivity due to brain damage from cerebral malaria, and loss of investment and tourism. In some countries with a heavy

malaria burden, the disease may account for as much as 40% of public health expenditure, 30-50% of inpatient admissions, and

up to 50% of outpatient visits.